Montana State Awarded $6.5M NASA Grant for Eclipse Research in 2023 and 2024

BOZEMAN – Several hundred undergraduate students from around the country will experience the zenith of 15 months of preparation on April 8, 2024, when the moon slips between Earth and the sun, completely blocking views of the sun for just over four minutes in parts of the continental United States.

Set up in several locations along the path of totality, which will stretch in the U.S. from southern Texas to northern Maine, the students will stay busy before, during and after those four minutes, launching high-altitude balloons, conducting scientific experiments and livestreaming video to NASA under the leadership of Montana State University’s Nationwide Eclipse Ballooning Project.

The program is the reprise of the 2017 Eclipse Ballooning Project founded at MSU eight years ago to give students an opportunity to conduct high-level science experiments during what was the first total solar eclipse visible from coast to coast in the U.S. in 99 years. It was so successful that the team followed up with expeditions to South America in 2019 and 2020, where the students launched more balloons during total eclipses and gathered data to advance general scientific knowledge through first-of-their-kind experiments.

This iteration of the program is being funded by a $6.5 million NASA grant that will cover the cost of equipment and supplies so that 800 to 1,000 students, about 25 of them from Montana, can be part of the next eclipse ballooning experience. The grant will fully support 70 teams from academic institutions around the U.S., selected based on proposals they submit by the end of this month.

This time, Montana’s engineering team will be based at MSU in Bozeman, while the atmospheric science team will be based at Salish Kootenai College, located in Pablo on the Flathead Indian Reservation. The tribal college was invited to lead the team thanks to funding from Space Grant, NASA’s higher education program focused on providing students hands-on opportunities that are useful in the workforce.

“NASA recognizes how important it is for students to get hands-on experience, and we try to accommodate students who would like the opportunity but have barriers,” said Angela Des Jardins, leader of the Nationwide Eclipse Ballooning Project, director of the Montana Space Grant Consortium and a professor in the Department of Physics in MSU’s College of Letters and Science.

That is exactly what having an opportunity to engage in a major scientific research project at will accomplish for his students, said Drew Grennell, Salish Kootenai’s Space Grant faculty affiliate and chair of the IT, Computer Science and Engineering Department at Salish Kootenai College.

“It’s hard to connect to opportunities on our campus that are very experiential as far as research or engineering applications,” Grennell said. “This is a great way for students to see what they could take part in if they continue to pursue a degree.

“NASA Space Grant values our students and is trying to incorporate and engage them in ways that serve them,” he added.

During an annular eclipse In October 2023, students will conduct experiments as the moon passes between the sun and Earth but does not completely block the sun. When it does completely block the sun on April 8, 2024, that total eclipse will be the last one visible in the United States until 2045, so NASA and MSU don’t want to miss it.

“Prior to the 2017 eclipse, there hadn’t been a total solar eclipse in the U.S. in a long time. To have another total eclipse happen in seven years is a great opportunity,” said Des Jardins.

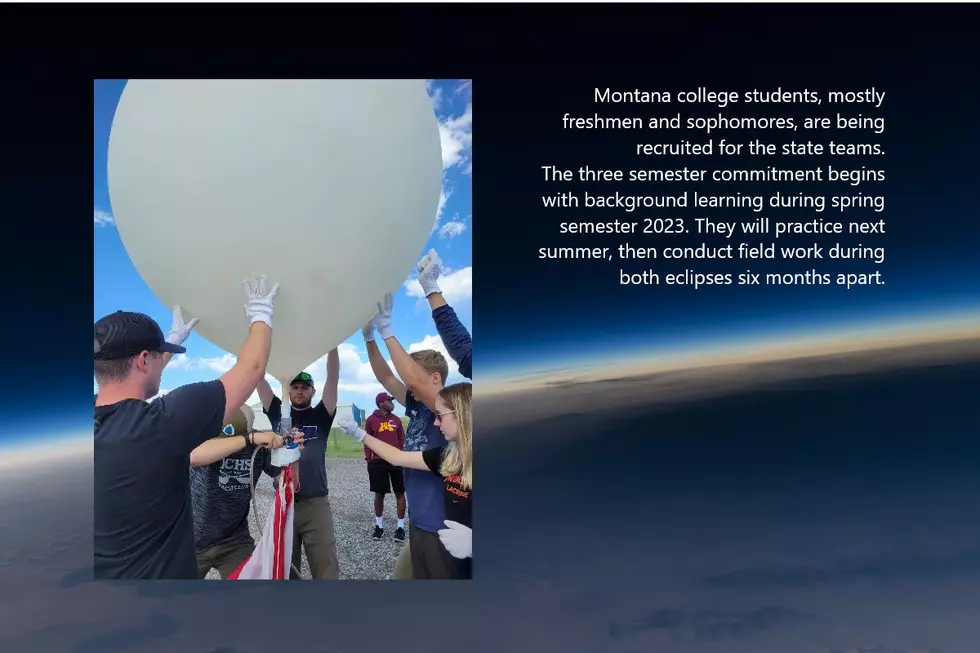

Montana college students, mostly freshmen and sophomores, are being recruited for the state teams. They will commit for three semesters, starting with background learning during spring semester 2023. They will practice next summer, then all that work will culminate in the field during both eclipses six months apart. It isn’t too late for students to apply to the program – those interested are invited to contact Des Jardins.

Eclipse Project balloons, unlike the colorful, teardrop-shaped hot air balloons used to carry people, are instead similar to the weather balloons that typically travel to an altitude of 100,000 feet, where the darkness of space and the curvature of the earth are visible.

The engineering teams will design, build and fly their own payload experiments, as well as assemble equipment that the balloons will carry to livestream video to NASA. Next fall’s eclipse will “in some ways be a dry run,” for the engineering teams, Des Jardins said, because the moon does not cast a shadow on the Earth during annular eclipses; however, the teams will practice using very precise GPS devices and helium control valves to keep the balloons at the desired altitude of 70,000 to 75,000 feet, where they will bounce along ripples in the atmosphere known as “gravity waves.”

Much of the engineering teams’ work will take place prior to the eclipses during the design-build process when they will be challenged to confine the payloads to a 12-pound limit.

“It pushes students’ ingenuity to keep light,” Des Jardins said.

The atmospheric science teams are charged with collecting data during both eclipses for later analysis. Each atmospheric science team will launch 30 balloons, one at a time, every hour for 30 hours. The balloons will carry ready-made sensors to collect data from the entire path of flight, from the ground up to 115,000 feet. The Eclipse Ballooning Project’s atmospheric team discovered in 2019 that the cool shadow cast by the moon during the total eclipse generated gravity waves in the upper atmosphere, so one question the student scientists will attempt to answer next October is whether gravity waves also are generated during annular eclipses.

Experts from NASA will serve as guides for students to ensure their experiments are designed correctly.

The endeavor “is a lot of work,” but Des Jardins said the fruits of the labor are invaluable.

“The goal of the Nationwide Eclipse Ballooning Project is to help students have hands-on, life-changing experiences to see if research is what they really want to do,” she said. “It’s important to give students the opportunity to know if science or engineering is actually something they would want to do for a career.”

More From KSEN AM 1150